Kīlauea Point Lighthouse & Wildlife Refuge

History, Birds, and Island Magic on Kauaʻi's Northern Shore

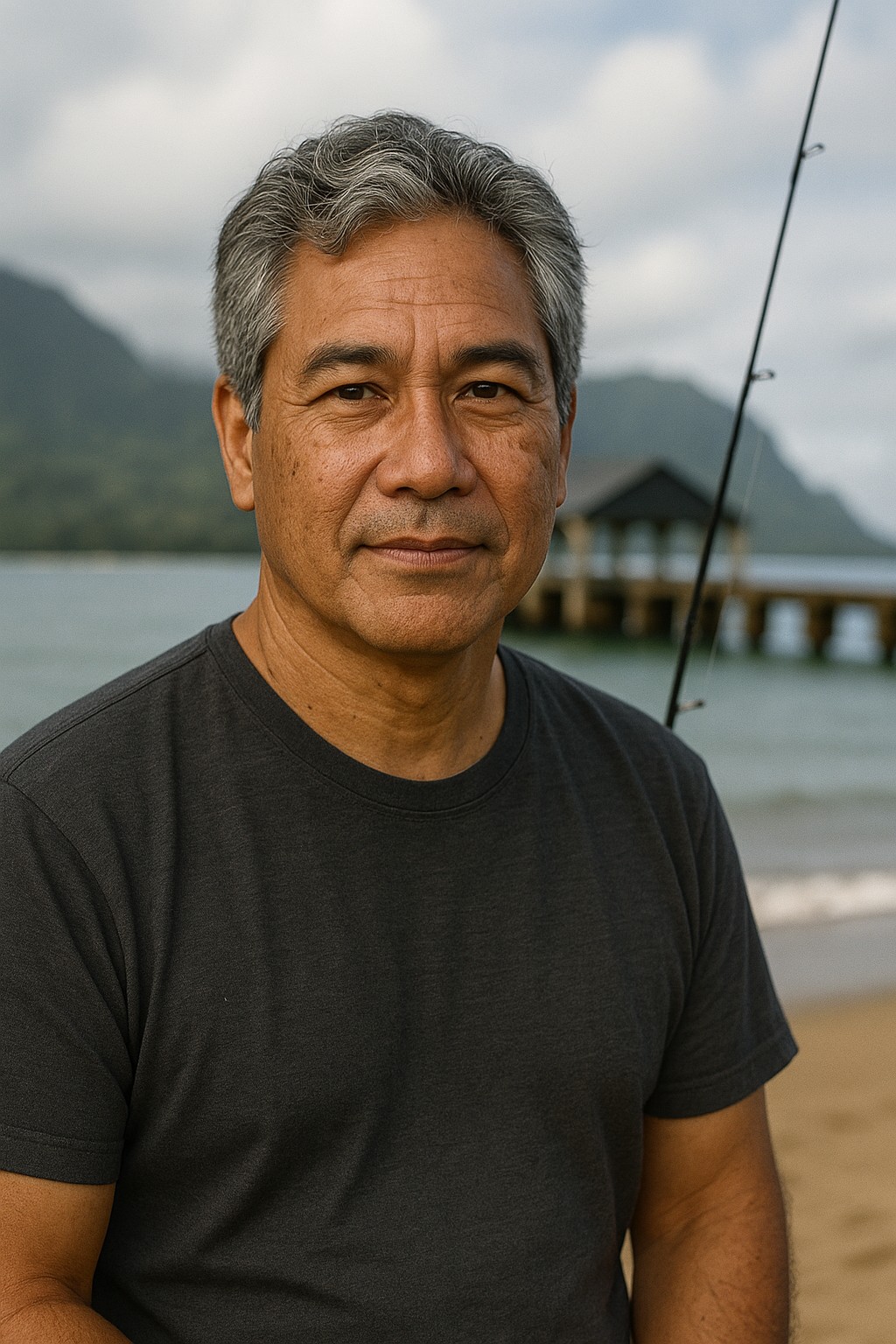

Written by a Kauaʻi Historian

Kalani MillerThe trade winds carry stories here. They whisper through the ironwood trees and dance around the white tower that stands watch over Kauaʻi's northern shore. I've been coming to this place since I was small, when my papa would pack us into the old truck and drive the winding road to what he called "the edge of the world."

Back then, the lighthouse still had its keepers. I remember meeting Sam Apana, one of the last men to tend the light. His weathered hands showed me how the great lens worked, how it caught sunlight and threw it back to sea. He told stories of nights when fog rolled in thick as poi, when ships depended on that beam to find safe harbor. Those memories shaped me before I understood their power.

Kīlauea Point isn't just a lighthouse or a bird sanctuary. It's a wahi pana, a sacred place where history lives in the concrete and coral, where the past speaks through the cry of seabirds, and where the future takes flight on wings that span seven feet.

Every wave that crashes against these ancient lava cliffs carries stories from across the Pacific. Every bird that nests here connects us to migration patterns older than human memory. This is my invitation to you. Come discover the Daniel K. Inouye Kīlauea Point Lighthouse and National Wildlife Refuge not as a tourist checking boxes, but as someone ready to connect with something bigger than yourself. Come prepared to listen. The land has much to teach.

The White Tower's Story: Built by Hand and Heart

In 1912, when ships from Asia crowded the Pacific trade routes, the U.S. government faced a growing problem. Vessels sailing east from the Orient needed a beacon to guide them safely to Hawaiian waters. The traffic was increasing yearly as trade between America and Asia expanded. Ships carried everything from silk and spices to machinery and dreams of prosperity.

Kauaʻi, sitting like a sentinel at the edge of paradise, was the obvious choice. But the decision didn't come easily. Government surveyors spent months studying wind patterns, ocean currents, and ship traffic. They interviewed steamship captains who knew these waters like the backs of their hands. The consensus was clear: Kauaʻi's northern shore was where ships first glimpsed land after weeks at sea.

The location picked itself. Kīlauea Point rises 180 feet above the ocean on the northernmost tip of the main Hawaiian Islands. That natural height meant builders could construct a shorter tower and save money. Smart planning that would serve ships for decades to come. The geological foundation was solid basalt, strong enough to support a lighthouse for centuries.

But this wasn't just about practicality. The point had been a navigation landmark for Polynesian voyagers long before European contact. Ancient navigators used the distinctive profile of the cliffs and the behavior of seabirds to guide their double-hulled canoes across vast ocean distances. The government was simply adding modern technology to an ancient navigation system.

Engineering Marvel and Human Grit

The Kīlauea Sugar Company sold the 31-acre site for one dollar. One dollar for a piece of land that would become one of Hawaiʻi's most treasured places. The company's generosity reflected a common understanding that lighthouse construction served everyone's interests. Sugar plantations depended on ships to carry their harvest to market. A lighthouse that prevented wrecks protected their livelihood too.

Construction began July 8, 1912. What happened next was part engineering marvel, part human grit. The 52-foot tower used a new technique called structural reinforced concrete. This was experimental stuff in 1912. Engineers were still learning how to combine steel rebar with concrete to create structures stronger than either material alone. Today, it's how we build the world.

The project attracted skilled workers from across the Hawaiian Islands and the mainland. Portuguese stonemasons, Japanese carpenters, and Hawaiian laborers worked side by side. Each group brought specialized skills. The Portuguese had generations of experience working with volcanic stone. Japanese carpenters understood precision joinery. Hawaiian workers knew the land, the weather patterns, and how to read the ocean's moods.

Getting materials to such a remote spot required creativity that would impress modern logistics experts. No roads existed on this part of Kauaʻi. The nearest port, Nawiliwili, lay twenty miles away over rough terrain. Everything came by sea. The lighthouse tender Kukui, a steam-powered workhorse, would anchor offshore while smaller boats carried supplies to a tiny cove. Workers cemented cleats directly into lava rock cliffs, then hoisted materials 110 feet up using wooden derricks and pure muscle.

🏗️ Construction Challenge

Weather added constant challenges. Trade winds that normally bring relief could turn violent without warning. Winter swells made landing supplies dangerous for months at a time.

💎 The Crown Jewel

A second-order Fresnel lens from Paris, crafted for $12,000, consisted of 1,008 individual glass prisms, each cut and polished by hand to exact specifications.

The French Lens Mystery

Here's where the story gets interesting. The assembly instructions were written entirely in French. Workers stared at the 4,000-pound lens components and French text they couldn't read. A urgent message went to Honolulu. Fred Edgecomb, an engineer who spoke French, traveled by ship to Nawiliwili Harbor, then rode horseback twenty miles to translate the documents.

Once assembled, the lens floated on 260 pounds of liquid mercury. This near-frictionless system let the massive structure rotate so smoothly you could move it with one finger. A weight-driven clockwork mechanism kept it turning all night long.

May 1, 1913 marked the official lighting. The dedication brought hundreds of locals who called their new landmark "our big lamp." Its double flash every ten seconds could save lives and guide dreams home.

Life at the Edge: The Lighthouse Keepers

Living at Kīlauea Point meant embracing isolation that most people today can't imagine. The station included the tower, an oil house, and three keeper homes built from blue volcanic rock quarried on-site. Each house had two bedrooms, a kitchen, bathroom, and concrete cisterns that collected rainwater from the roof. These weren't luxury accommodations. They were functional shelters designed to house families at the edge of the world.

The keepers lived by the rhythm of sun and sea. Their routine never changed and couldn't be compromised. Light the lamp at sunset. Keep watch through the night. Wind the clockwork mechanism every three and a half hours. Extinguish the flame at sunrise. Polish brass. Clean glass prisms. Maintain the grounds. Check oil levels. Record weather observations. Write detailed logs that documented everything from wind direction to ship sightings.

Supplies arrived monthly if weather permitted. The lighthouse tender brought mail, food, fresh water, kerosene, and news from the outside world. When storms prevented deliveries, families survived on whatever they could find or grow. One keeper's son remembered his father hunting wild goats on horseback to feed everyone. Fishing from the cliffs provided protein when other sources ran low.

Children at the station lived unique lives. They attended school by correspondence when possible, but often learned from whatever books and materials were available. They played in tide pools, explored sea caves, and grew up knowing the names and habits of every bird species on the point. Their playground was one of the most beautiful and dangerous places on earth.

Samuel Apollo Amalu: Master of All Trades

Samuel Apollo Amalu embodied the keeper spirit during his tenure from 1915 to 1924. This native Hawaiian represented the best of lighthouse service. Born on Molokaʻi, he understood island life in ways that mainland keepers couldn't match. He could read weather patterns in cloud formations, predict storms from the behavior of seabirds, and navigate treacherous waters that intimidated experienced sailors.

Amalu earned the U.S. Lighthouse Service efficiency flag three years running for his excellent maintenance. His station consistently ranked among the best in the Pacific. Visiting inspectors found spotless quarters, perfectly maintained equipment, and detailed logs that read like maritime poetry. Amalu called lighthouse keeping a job for "masters of all trades." You needed skills as a machinist, carpenter, painter, engineer, meteorologist, and diplomat.

His swimming ability became legendary. Amalu would brave rough waters and sharks to reach Mokuʻaeʻae, the small rocky island offshore. He did this to check on the automated fog signal and to collect seabird eggs when food ran short. Local fishing families respected his courage and skill in conditions that claimed other strong swimmers.

Explore Kīlauea Point Lighthouse

Discover the complete story of this sacred place—from dramatic wartime rescue to incredible wildlife and practical visitor information.

ℹ️ Quick Info

- Hours: Wed-Sat 10am-4pm

- Entry Fee: $10 per adult

- Reservation: Required

- Book At: Recreation.gov

- Book Ahead: Up to 60 days

🌅 Best Times to Visit

- Albatross Courtship Nov-Dec

- Humpback Whales Jan-Mar

- Albatross Chicks Jan-Jun

- Fledging Season July

🎒 What to Bring

- Binoculars (essential!)

- Camera with zoom lens

- Sunscreen & hat

- Light rain jacket

- Water (only liquid allowed)