“Brew Your Best Cup”- Coffee Brewing Workshop

Heavenly Hawaiian Coffee Farm • Farm • Holualoa, Island of Hawaii • Hawaii

Kings and queens who shaped our islands with courage, wisdom, and aloha

Written by a Local Cultural Guide

Leilani AkoBefore there was one Hawaii, there were many kingdoms scattered across our island chain. Warfare was common. Peace was rare. Into this world was born a chief destined to change everything—Kamehameha I, known as the Great.

The prophecy said that whoever could move the Naha Stone would unite the Hawaiian Islands. This massive rock, weighing over two tons, sat unmoved for generations. When young Kamehameha lifted it, he set in motion events that would forge our modern Hawaii.

Kamehameha's conquest wasn't just about battles, though he fought many. He was a master diplomat who understood that true strength comes from bringing people together. By 1810, he had peacefully united all the Hawaiian Islands under one rule for the first time in our history.

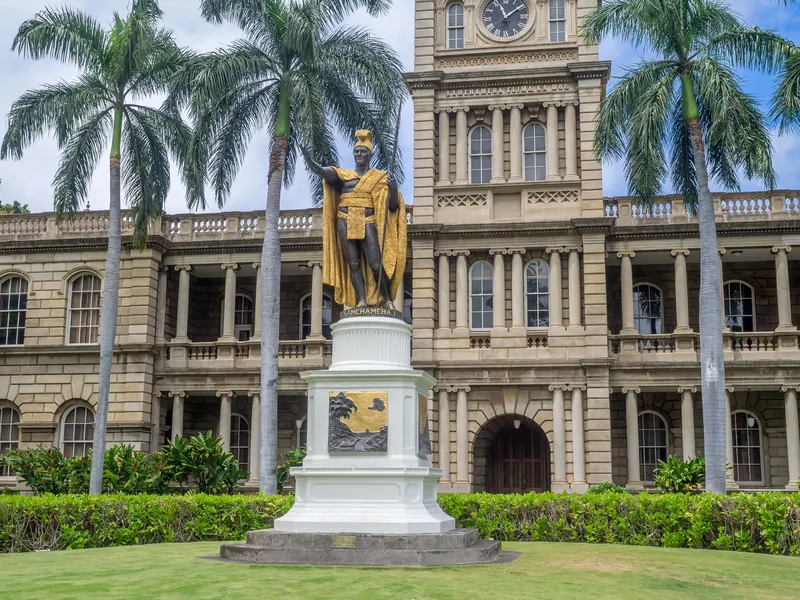

The most famous statue of Kamehameha I stands in downtown Honolulu, right in front of Aliʻiōlani Hale. Created by American sculptor Thomas Ridgeway Gould, this bronze giant has watched over our capital city since 1883.

I've brought countless visitors here, and they always ask about his cape. That's a traditional feather cape, or ʻahuʻula, made from thousands of tiny bird feathers. In real life, only the highest chiefs wore these sacred garments. The statue shows Kamehameha in full royal regalia—feather cape, helmet, and traditional malo.

Every June 11, on King Kamehameha Day, our community comes together for the lei draping ceremony. Hundreds of fresh lei cascade down his bronze form. Yellow and orange marigolds, purple orchids, white plumeria—the colors tell their own story of our diverse yet united islands.

I bring my children to this ceremony every year. Last year, Nalu tried to climb the statue's base to get a better view. "Mama, why is he so tall?" he asked. "Because his spirit is tall too," I told him. "He had to be big enough to hold all of Hawaii in his heart."

The most fascinating Kamehameha statue isn't in Honolulu—it's in tiny Kapaʻau on Hawaii's Big Island. This bronze sculpture has a story that sounds like fiction but is absolutely true.

This statue was actually cast first, meant for Honolulu. But during shipping in 1880, the vessel carrying it sank near the Falkland Islands. The ship's captain sold the "lost" statue for scrap metal to recover some costs. Meanwhile, a replacement was quickly commissioned for Honolulu.

Here's where it gets amazing. The original statue was recovered from the wreck and eventually made its way to Hawaii anyway. Instead of fighting over which statue belonged where, our community decided the recovered statue should go to Kapaʻau, near where Kamehameha was actually born.

I've visited Kapaʻau many times with cultural groups. The statue stands in front of an old courthouse, painted in bright colors that some art critics call "garish." But the local community fought to keep those colors. They represent how local people see their king—not as a museum piece, but as a living part of their daily lives.

The restoration of this statue in recent years became a community effort. Local families, Hawaiian civic clubs, and cultural organizations all contributed. They didn't want it to look like a pristine museum display. They wanted their Kamehameha to reflect their own identity and pride.

Downtown Honolulu's iconic guardian since 1883, famous for annual lei draping ceremony.

The original statue recovered from shipwreck, colorfully restored by the local community.

Overlooking Hilo Bay surrounded by lush tropical plants, connecting to nature.

In Hilo's Wailoa River State Park stands another Kamehameha statue, this one originally intended for Kauai. When plans for that statue fell through, Hilo claimed it. The irony is perfect—this statue overlooks Hilo Bay, where Kamehameha established one of his first seats of government.

This statue feels different from the others. Surrounded by lush tropical plants and facing the bay, it seems more connected to nature. When I take my family there, we often see local fishermen casting nets nearby, just as their ancestors did in Kamehameha's time.

Few visitors know that Hawaii has a Kamehameha statue in our nation's capital. Standing in the National Statuary Hall, it represents Hawaii's contribution to American history. Each state gets two statues in this collection, and Kamehameha is one of ours.

This statue reminds mainland visitors that Hawaii's history didn't begin with statehood in 1959. We were a sovereign nation with our own great leaders long before we joined the United States.

King Kamehameha Day

Queen Liliʻuokalani Birthday

Prince Kūhiō Day

Between ʻIolani Palace and the Hawaii State Capitol stands a statue that always brings tears to my eyes. Queen Liliʻuokalani, Hawaii's last reigning monarch, holds three objects that tell the story of her life and our loss.

In her hands are the Hawaiian constitution she tried to promulgate, a copy of "Aloha ʻOe" (the song she composed), and the Kumulipo, our creation chant. These items represent her roles as political leader, cultural artist, and keeper of Hawaiian traditions.

Liliʻuokalani became queen in 1891, inheriting a kingdom under threat from foreign business interests. She tried to restore power to the Hawaiian people through a new constitution, but this led to her overthrow in 1893. She spent the rest of her life fighting for Hawaiian rights and preserving our culture.

The statue's placement tells its own story. She stands between the palace where she once ruled and the state capitol where others now govern. It's a powerful reminder of what we lost and what we still hope to reclaim.

I often bring my hula students here when we're studying songs about Hawaiian royalty. "Look at her face," I tell them. "She's not defeated. She's determined." Even in bronze, Queen Liliʻuokalani radiates the strength that helped her survive imprisonment and continue fighting for her people.

Every year on her birthday, September 2, our community gathers here for a memorial service. We sing "Aloha ʻOe" and drape her statue with lei. It's one of the most moving ceremonies in Hawaii, connecting us directly to our sovereign past.

In Waikiki's Kaiulani Triangle Park stands a statue that most tourists walk past without knowing her story. Princess Kaʻiulani was Queen Liliʻuokalani's niece and heir to the Hawaiian throne. Her story is one of promise cut tragically short.

Born in 1875, Kaʻiulani was brilliant, beautiful, and bicultural. Her father was Scottish businessman Archibald Cleghorn, her mother was Princess Miriam Likelike. She grew up speaking Hawaiian, English, and French, preparing for her future role as queen.

The statue shows her with peacocks, which roamed freely on her Waikiki estate. These exotic birds became her symbol, representing both her unique position and her love of beautiful things. She kept them as pets and was often photographed with them.

When the Hawaiian Kingdom was overthrown in 1893, eighteen-year-old Kaʻiulani was studying in Europe. She traveled to Washington D.C. to meet with President Grover Cleveland, pleading for her people's rights. "I am a daughter of Hawaii," she told American officials. "Please do not let them take away our independence."

Her diplomatic efforts were brave but unsuccessful. She returned to Hawaii heartbroken and died in 1899 at just twenty-three years old. Many believe she died of a broken heart over her lost kingdom.

I always pause at her statue when I'm walking through Waikiki with my children. Malia, who's about the same age Kaʻiulani was when she first traveled to the mainland, always asks about the peacocks. I tell her about a princess who was smart and brave but lived in very difficult times.

At Kuhio Beach in Waikiki stands the statue of Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole, known as the "Prince of the People." While other royalty focused on diplomacy with foreign powers, Kūhiō dedicated his life to helping ordinary Hawaiians.

Born in 1871 on Kauai, Kūhiō was Queen Liliʻuokalani's nephew. After the overthrow, he could have retreated into private life. Instead, he chose public service. In 1902, he became Hawaii's delegate to the U.S. Congress, a position he held for twenty years.

Kūhiō's greatest achievement was the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act of 1921. This law set aside 200,000 acres of land for Native Hawaiian homesteading. It wasn't perfect—much of the land was unsuitable for farming—but it was the first federal recognition of Native Hawaiian rights.

The statue shows Kūhiō holding a scroll, representing the Hawaiian Homes Act. He's dressed in Western clothing, reflecting his role as a bridge between Hawaiian and American cultures. His expression is serious but kind, matching descriptions of his personality from people who knew him.

Every year on March 26, Prince Kūhiō Day, we celebrate his contributions with festivals across the islands. It's a state holiday that reminds us how one person's dedication can create lasting change. I always tell my children that Kūhiō proved you don't need a crown to serve your people—you just need a caring heart.

At the corner of Kalakaua and Kuhio Avenues in Waikiki stands a statue of the king who saved Hawaiian culture. David Kalākaua, known as the "Merrie Monarch," ruled from 1874 to 1891 and is beloved for reviving hula and other Hawaiian traditions.

Before Kalākaua's reign, Christian missionaries had suppressed many Hawaiian cultural practices, including hula. They called our sacred dance "heathen" and "immoral." Kalākaua understood that culture is the soul of a people, and he brought hula back to public life.

In 1883, Kalākaua's coronation ceremony featured the first public hula performance in decades. He also supported the compilation of Hawaiian legends, the preservation of Hawaiian language, and the continuation of traditional crafts. Without his efforts, much of what we celebrate today might have been lost forever.

The statue was dedicated on the anniversary of the arrival of the first Japanese laborers in Hawaii, acknowledging Kalākaua's role in international diplomacy. He traveled around the world, the first reigning monarch to do so, building relationships that brought diverse communities to our islands.

As someone who learned hula from my tutu and now teaches it to others, I owe a debt to King Kalākaua. Every time I watch keiki learning their first hula steps, I remember that this art form survived because one king understood its importance.

Heavenly Hawaiian Coffee Farm • Farm • Holualoa, Island of Hawaii • Hawaii