Kōloa's Living History

Discovering the Heart of Kauaʻi's South Shore

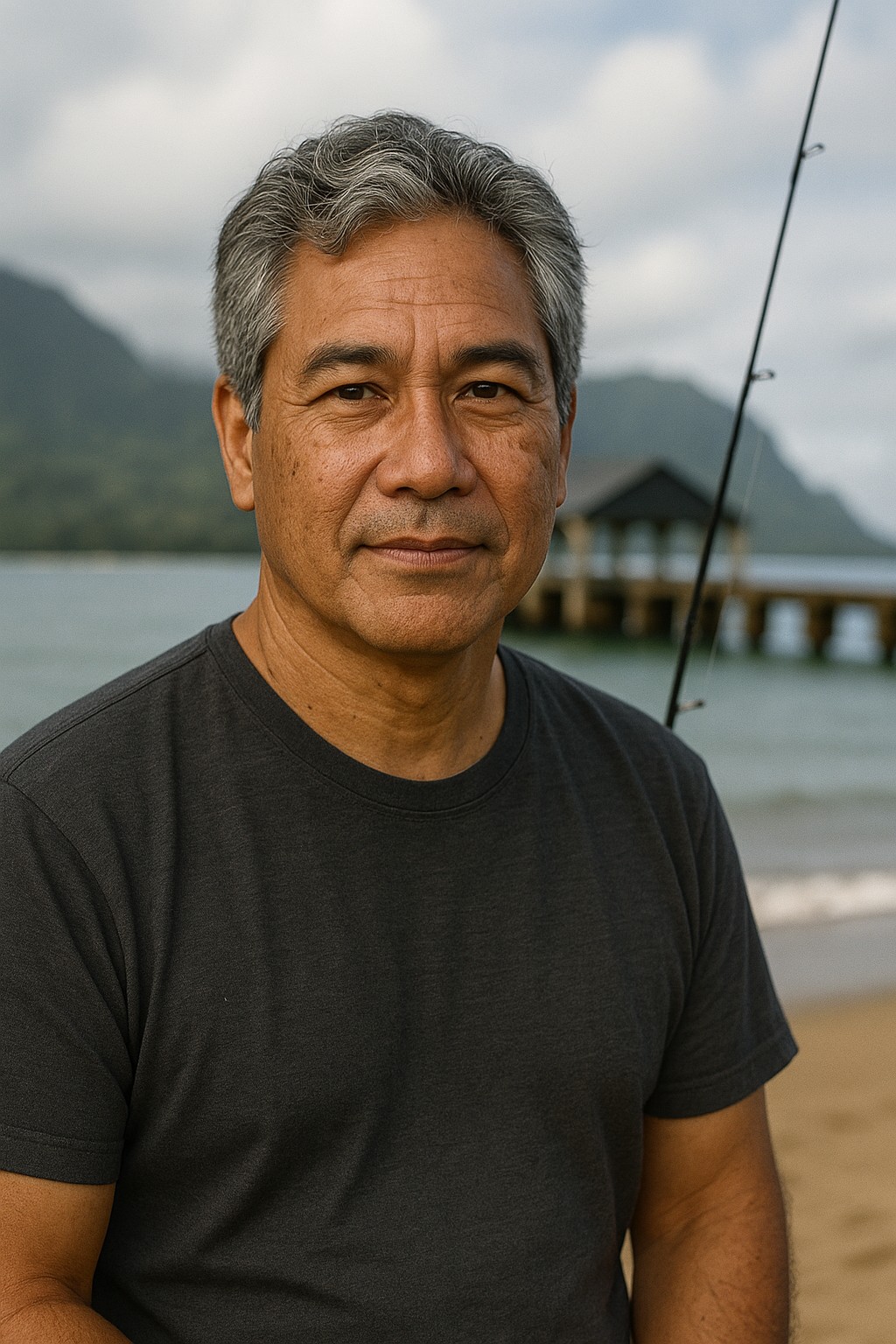

Written by a Local Kauaʻi Expert

Kalani MillerI still remember the feeling of my small hand in my grandmother's, walking down Kōloa Road on a warm afternoon. The air was a mix of familiar scents: the salty-sweet smoke of teriyaki burgers grilling at the Sueoka Store Snack Shop, the heavy perfume of plumeria blossoms, and the cool, earthy shade cast by the giant monkeypod trees that have watched over this town for generations. She would point a gentle finger toward the old, false-front buildings, their paint faded by a century of sun and sea spray, and tell me, "This isn't just a town, keiki. It's a storybook."

She was right. To the passing eye, Old Kōloa Town is a charming collection of boutiques and eateries on Kauaʻi's sunny South Shore, a convenient stop on the way to the beaches of Poʻipū. But to truly understand this place, you have to learn to read its stories. This isn't just a destination. It's a living museum, a place where the soul of Kauaʻi's plantation era is still palpable on every corner, in the family names on the storefronts, and in the flavors of the food.

This is my invitation to you to step into that storybook. We'll go far beyond a simple list of shops and restaurants. Together, we'll uncover the complex, bittersweet history of the Kōloa Sugar Mill, the first of its kind in Hawaiʻi, and meet the diverse people from around the world who built this community with their sweat and sacrifice.

The Story of Kōloa: From King Sugar's Reign to Historic Gem

To understand Kōloa is to understand the story of sugar in Hawaiʻi. It's a tale of innovation, ambition, hardship, and the unlikely creation of the multicultural society that defines our islands today. The story begins right here, on this fertile patch of land on Kauaʻi's South Shore.

The Birth of an Industry: The Kōloa Mill and a New Hawaiʻi (1835-1850)

In 1835, when the American firm Ladd & Company leased 980 acres from King Kamehameha III to cultivate sugarcane, they weren't just starting a farm. They were planting the seeds of a revolution that would change Hawaiʻi forever. While Native Hawaiians had grown kō (sugarcane) for centuries in small personal plots, this was the first attempt at large-scale commercial production. The choice of Kōloa was strategic: the soil was rich, a nearby harbor offered access to markets, and a waterfall at Maulili pool provided the raw power needed for milling.

The venture's first manager, a Bostonian named William Hooper, arrived at the age of 24 with no practical experience in agriculture, engineering, or Hawaiian culture. The challenges were immense. Local chiefs, wary of the foreign enterprise, initially withheld provisions, and the local workforce was unaccustomed to the Western concept of wage labor. The first mill, equipped with wooden rollers, quickly wore out, producing only molasses in its first year. Undeterred, Ladd & Co. invested in iron rollers, and in 1837, the mill produced its first real crop: 4,286 pounds of sugar and 2,700 gallons of molasses. This marked the birth of Hawaii's sugar industry.

Between 1839 and 1841, a new, more substantial mill was built on the Waihohonu Stream at a cost of nearly $16,000. It is the iconic stone chimney from this second mill that stands today as a silent monument to that era, a National Historic Landmark since 1962.

But this "success" came at a great human cost. The foundation of this new economy was built on an exploitative labor system. Native Hawaiian workers were paid a meager $2 per month, not in cash, but in "Kauai Currency"—scrip that could only be redeemed at the plantation store, where goods were sold at inflated prices. In 1841, this simmering tension boiled over. In the first recorded labor strike in Hawaiian history, workers walked off the job, demanding their pay be doubled to 25 cents a day. The plantation owners refused, and the strike was quickly suppressed, but it was a powerful act of resistance that foreshadowed the century of labor struggles to come.

The Human Engine: Forging a Multi-Ethnic Society in the Cane Fields

As the sugar industry boomed across the islands, the demand for labor became insatiable. The Native Hawaiian population, tragically decimated by Western diseases, was declining, and many resisted the harsh conditions and restrictive contracts of plantation life. The planters' solution was to import labor on a massive scale, scouring the globe for workers. This decision would irrevocably shape the demographic and cultural landscape of Hawaiʻi.

The planters orchestrated a deliberate strategy of "divide and rule." They recruited workers from different countries and systematically housed them in separate ethnic camps—Japanese, Chinese, Portuguese, Filipino—and paid them different wages for the exact same work. The goal was to foster distrust, prevent the workforce from uniting, and keep wages brutally low. The luna, or overseer, often on horseback with a whip, became a symbol of this oppressive hierarchy.

Yet, something remarkable and unintended happened in those fields. The shared experience of back-breaking labor under a hot sun, the common struggle against the plantation system, and the simple, human need to communicate across language barriers created a powerful bond. The planters' strategy of division paradoxically became the catalyst for unification. From this crucible of hardship, a new, shared identity began to form. This is where the modern, multicultural soul of Hawaiʻi was truly born—not through a gentle blending, but as an act of profound resilience.

The Stories of the People

My tūtū kāne (grandfather) used to say that you could taste the whole world in a single plate lunch. He was talking about the legacy of the people who came to Kōloa, each group bringing their culture, food, and traditions, which eventually blended into the local culture we cherish today.

🇨🇳 The Chinese (Arrived 1852)

The first contract laborers to arrive were from China. Some came as skilled "sugar masters" who understood the refining process, while others were farmers seeking opportunity. After their contracts ended, many left the plantations to become merchants and entrepreneurs, establishing the small shops and businesses that formed the backbone of towns like Kōloa.

🇯🇵 The Japanese (Arrived 1868)

The first group of Japanese workers, the Gannen-mono ("first-year people"), arrived in 1868. Life was incredibly difficult, a reality they captured in mournful folk songs called holehole bushi. Yet, they built strong communities, establishing institutions like the Kōloa Jodo Mission in 1910, a Buddhist temple that still stands today.

🇵🇹 The Portuguese (Arrived 1878)

Unlike other groups who were primarily single men, Portuguese immigrants from the Madeira and Azores islands were encouraged to bring their families. They brought their devout Catholic faith, founding St. Raphael's Catholic Church in 1841, and their love for baking, building traditional stone ovens to make sweet bread.

🇵🇭 The Filipino (Arrived 1906)

The last major wave of immigrants, known as sakadas, came from the Philippines. They were often assigned the most physically demanding jobs for the lowest wages. Filipino leaders like Pablo Manlapit were instrumental in organizing the labor movement, leading major strikes in 1920 and 1924.

Out of this melting pot of languages and cultures, Hawaiian Pidgin English emerged—not as a broken form of English, but as a complex and legitimate language created out of necessity so that Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese, Filipino, and Hawaiian workers could understand one another in the fields.

The End of an Era: From Mill to Monument (1900-Present)

As the 20th century progressed, the Kōloa plantation, like many others, was absorbed by one of the "Big Five" corporations that dominated the islands' economy—in this case, Alexander & Baldwin. In 1912, the old mill was replaced by a much larger, more modern facility to the east. For another 84 years, the rhythms of Kōloa were dictated by the mill whistle. But the reign of King Sugar was waning. On October 25, 1996, the Kōloa mill processed its final load of sugarcane and fell silent, ending 161 years of continuous operation.

The closure marked the end of an era, but not the end of Kōloa's story. Through the foresight of community members and preservationists, the old town was saved from demolition. Its historic buildings were carefully restored, preserving the architectural character of the plantation days. Today, Old Kōloa Town stands as a tribute to its complex past—a place where history is not just remembered, but lived in and shared every day.

Explore Old Kōloa Town

Walk through history, taste multicultural flavors, and discover the living heritage of Kauaʻi's South Shore.

ℹ️ Quick Info

- Location: South Shore

- Founded: 1835

- Best Time: Year-round

- Parking: Free lots

- Time Needed: 2-4 hours

⭐ Must-See

- Sugar Monument

- Kōloa Jodo Mission

- Tree Tunnel

- Historic Buildings

- Monkeypod Tree

📅 Best Times

Late July (10-day festival)

Third Saturday each month

Before 10am or after 3pm