Resistance & Resilience

Hawaiian Adaptation, Survival, and the Wilcox Legacy

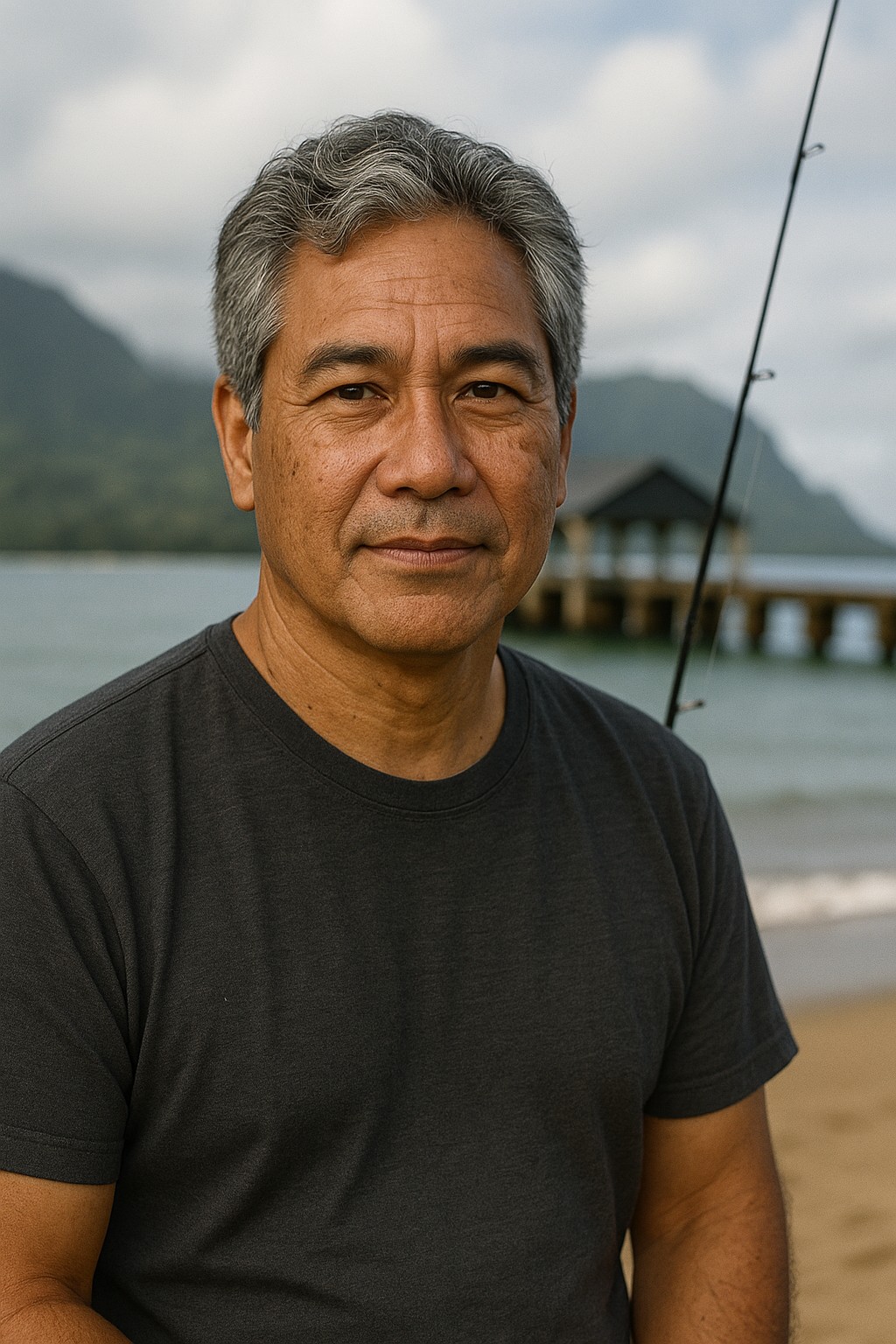

Written by a Local Cultural Historian

Kalani MillerCultural Suppression: The Price of Salvation

The missionary project, by its very nature, required the suppression of traditional Hawaiian culture. Missionaries viewed indigenous spiritual practices not as different ways of understanding the world, but as "heathenism" that needed to be eliminated for the salvation of Hawaiian souls.

The most famous casualty was hula, the sacred dance that was central to Hawaiian religious and cultural expression. Missionaries condemned hula as "lascivious" and associated with "idolatry." They convinced the powerful regent Kaʻahumanu to outlaw the practice in 1830, driving it underground where it survived in secret among Hawaiian families who refused to abandon their traditions.

Traditional chanting, another fundamental expression of Hawaiian culture, faced similar suppression. The oli (chants) that preserved genealogies, histories, and spiritual knowledge were replaced with Christian hymns and prayers. While some chants survived in modified form, much of this oral tradition was lost or fragmented.

Missionaries also discouraged traditional healing practices, dismissing native medicine as superstition despite its effectiveness in treating many ailments. They established Western-style schools that ignored traditional Hawaiian knowledge systems, creating generations of Hawaiian children who were cut off from their ancestral wisdom.

The Hawaiian language itself came under attack in later decades. While early missionaries had promoted literacy in Hawaiian, their descendants and other Western educators began pushing for English-only instruction. By the end of the 19th century, Hawaiian-language schools were being replaced with English-medium institutions that treated Hawaiian as a barrier to progress rather than a treasure to be preserved.

Religious practices centered on sacred sites were particularly targeted. Missionaries destroyed or abandoned heiau (temples) and other religious structures, replacing them with Christian churches. They discouraged offerings to traditional deities and the spiritual practices that connected Hawaiians to their ancestral lands.

Seeds of Resistance: Hawaiian Agency and Adaptation

Despite the overwhelming pressure to abandon their traditions, Hawaiians demonstrated remarkable resilience and creativity in preserving their culture. They didn't simply accept missionary teachings passively but actively negotiated and adapted them to fit their own worldview and needs.

Many Hawaiians became sincere Christians while maintaining elements of their traditional beliefs. They interpreted Christian concepts through Hawaiian cultural frameworks, creating a syncretic religious practice that satisfied missionary expectations while preserving indigenous wisdom. Stories of Jesus were told using Hawaiian narrative traditions, and Christian holidays were celebrated with modified versions of traditional practices.

Hawaiian scholars used the literacy skills taught by missionaries to record and preserve traditional knowledge. They wrote down chants, stories, and historical accounts in Hawaiian, creating a written record that survived the cultural suppression of later periods. These documents now serve as invaluable resources for cultural practitioners working to revitalize Hawaiian traditions.

The Hawaiian-language press became a powerful tool for cultural preservation and political resistance. Newspapers like Ka Nupepa Kuokoa and Ke Au Okoa published traditional stories alongside contemporary news, keeping Hawaiian cultural knowledge alive in written form. They also provided forums for discussing political issues and organizing resistance to American annexation.

Hawaiian musicians transformed Christian hymns and Western musical forms, creating new genres that preserved Hawaiian aesthetic values while satisfying missionary requirements. The development of slack-key guitar and the unique Hawaiian style of singing Christian songs in four-part harmony represented creative adaptations that enriched both traditions.

Political leaders like Queen Liliʻuokalani used their Western education and Christian faith to defend Hawaiian sovereignty. They argued that Christian principles of justice and self-determination supported Hawaiian independence rather than American domination. Their sophisticated legal and diplomatic efforts demonstrated how Western tools could be used to protect Hawaiian interests.

The Wilcox Legacy: Bridging Worlds

The seven Wilcox sons who grew up in the Mission House embodied the complex legacy of the missionary era. Raised in a household that valued both Christian faith and Hawaiian culture, they became prominent figures who helped shape modern Hawaiʻi while maintaining connections to both sides of their heritage.

George Wilcox became one of Kauaʻi's most successful businessmen, founding Grove Farm Plantation and pioneering innovative agricultural techniques. He employed hundreds of Hawaiian workers and maintained paternalistic but genuine concern for their welfare. His business success demonstrated how missionary values of hard work and education could lead to economic advancement in the changing Hawaiian economy.

Albert Wilcox served in the Hawaiian Legislature and later in the Territorial government after annexation. He advocated for Hawaiian rights and opposed some of the more exploitative practices of other plantation owners. His political career showed how missionary-educated Hawaiians could work within Western political systems to protect indigenous interests.

Samuel Wilcox became a prominent educator and community leader. He founded schools and supported efforts to preserve Hawaiian culture and language. His work demonstrated how Western educational methods could be used to strengthen rather than undermine Hawaiian identity.

The Wilcox brothers' success came at a cost, however. Their wealth and status depended on economic systems that had displaced many Hawaiian families from their ancestral lands. Their positions of leadership were possible partly because they had been educated in Western ways that other Hawaiians lacked access to. This created tensions within the Hawaiian community about collaboration versus resistance.

Despite these contradictions, the Wilcox family maintained strong connections to Hawaiian culture throughout their lives. They spoke Hawaiian fluently, supported Hawaiian musicians and artists, and advocated for policies that benefited the broader Hawaiian community. Their example showed how individuals could navigate between two worlds while maintaining integrity to both.

Continue the Journey

Explore more of the Waiʻoli Mission story

ℹ️ Quick Info

- Location: Hanalei, Kauaʻi

- Built: 1837 (House)

- Church Built: 1912

- Tours: Tue, Thu, Sat

- Cost: By donation

- Phone: (808) 826-1528

👨👦👦 Wilcox Brothers

- George - Businessman

- Albert - Legislator

- Samuel - Educator

- Plus 4 more brothers

✊ Forms of Resistance

- Secret hula practice

- Hawaiian-language press

- Recording traditions

- Musical adaptation