The Sound of Creation

Understanding the Traditional Foundations of Hawaiian Art

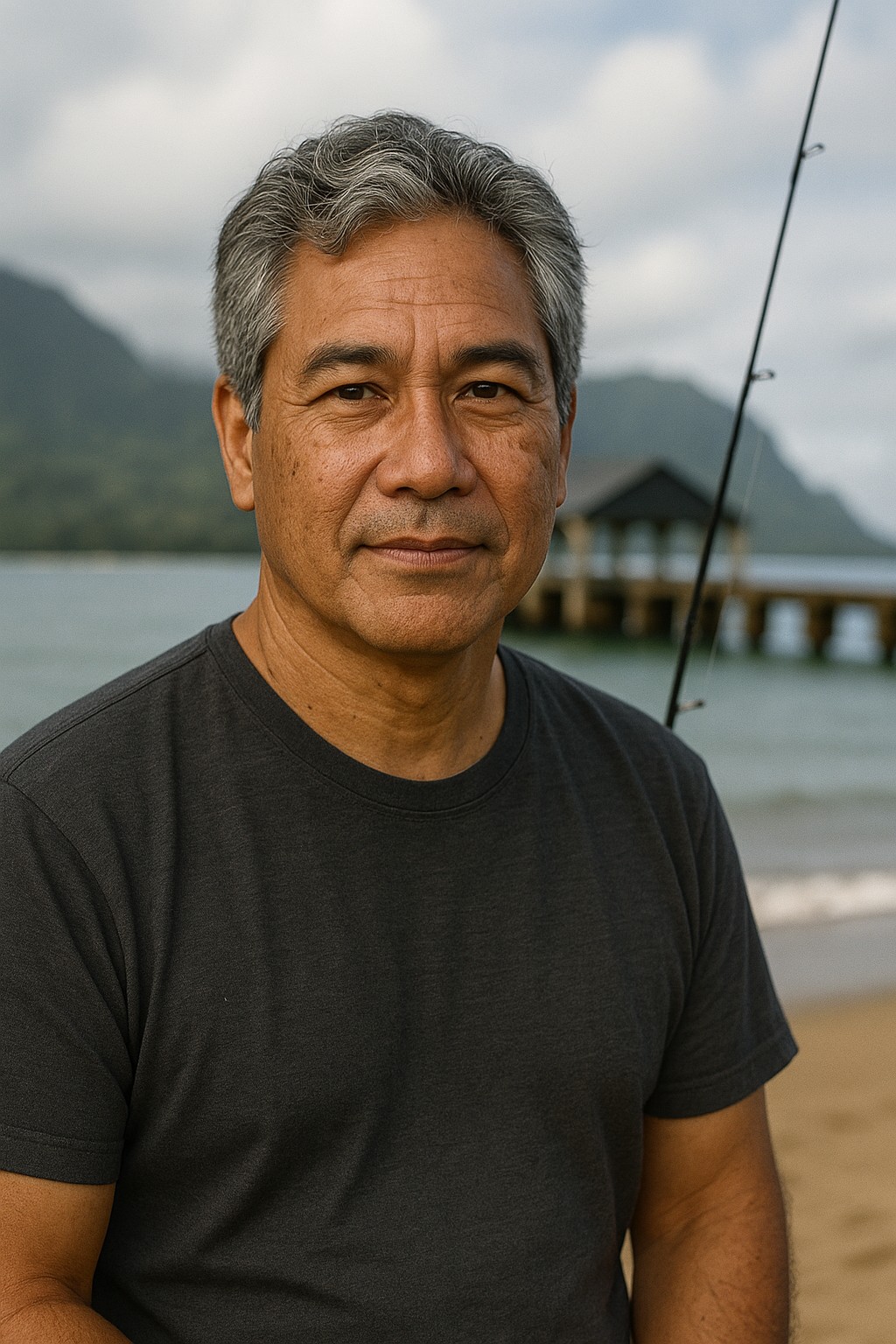

Written by a Cultural Expert

Kalani MillerThe First Marks – Reading the Stories in Stone

My journey starts on the Island of Hawaiʻi. I stand on the boardwalk looking over the Puʻu Loa petroglyph fields. The name means "Hill of Long Life." A fitting title for a place that holds over 23,000 images. Some etched into stone centuries ago.

These are the kiʻi pōhaku, or rock images. They represent the first storytellers of Hawaiʻi. Carved through the dark volcanic crust of a pāhoehoe lava flow, they show human figures, canoes, turtles, and abstract patterns.

While their exact meanings are lost in time, scholars believe they are records of life itself. They mark births, deaths, journeys, and other big events. In a culture that had no written alphabet, this was a public library.

The act of carving was a way to claim domain. To mark a place with a story. To create a lasting message for generations to come.

Looking out at the stark, beautiful canvas of black lava, I realize this is the birth of public art in Hawaiʻi. The medium changed from volcanic rock to concrete walls. But the basic drive to publicly declare, "we are here, this is our story, this is our land," is a tradition that has never been broken. It is an ancient and powerful statement of presence and belonging.

The Beating Heart of Kapa – Crafting with Kumu Dalani Tanahy

From the deep silence of the petroglyphs, I travel to Oʻahu and into a world of sound. In the back garden of a home in Mākaha, the air hums with a rhythmic, strong pulse. It is the ʻouʻou, the sound of wooden beaters striking wet bark. A sound that once echoed across the islands.

I am at the home studio of Dalani Tanahy. A master practitioner and founder of Kapa Hawaii. She leads a revival of this nearly lost art form.

Artist Spotlight: Dalani Tanahy

Dalani's journey is one of deep dedication. With the art of kapa making considered lost by the late 1800s, she and other practitioners have spent decades researching museum collections. Studying historical texts. Learning through tireless trial to bring it back to life.

"There were no more wauke trees, I had to grow them," she says. "There were no tools, I had to carve and gather them."

Her philosophy shows deep respect for the medium itself. She avoids drawing realistic pictures on her kapa. "I feel like once there's a picture the focus is on the picture not the canvas. And this is way much more than a canvas." For her, the traditional geometric patterns become part of the kapa. They honor the material rather than overshadowing it.

Today, her creations are not just hung on walls. They are used for sacred purposes. As ceremonial clothing (pāʻū) for hula. As blankets for newborns. As burial shrouds. Re-integrating this ancient art into the most important moments of modern Hawaiian life.

She hands me a stalk of the wauke plant, or paper mulberry. She grows it herself. "Without the trees, you don't have the kapa," she tells me. The art begins with growing plants.

The process is hard and humbling. I learn to strip the inner bark, the bast fiber. Soak it until it begins to rot. Then comes the beating. With a heavy wooden beater called an iʻe kuku on a wooden anvil known as a kua lāʻau, I join the chorus. My arms ache quickly. A proof of the strength and endurance of the women who traditionally did this work.

This sound, Dalani explains, was more than just the sound of labor. It was a form of talk. A soundscape of home that was almost wiped out by colonization and the arrival of cotton in the 1800s. Its revival is an act of auditory reclamation.

As my muscles burn from the repetitive motion of beating the fibers, I realize what I am doing is more than a craft workshop. It is a powerful act of cultural sovereignty in miniature. Making kapa is not just making cloth. It is the embodiment of self-determination.

🎨 Traditional Arts

- Kiʻi Pōhaku: 23,000+ images

- Kapa Revival: 1980s-present

- Featherwork: 450,000 feathers

- Wood Types: Koa, ʻōhiʻa

🌿 Sacred Materials

- Wauke (Paper Mulberry)

- Mamo Bird Feathers

- Koa Wood

- Volcanic Rock

- Olonā Fiber

📍 Learning Locations

Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park

Mākaha, Oʻahu

Honolulu featherwork collection

Sacred kiʻi guardians

🧭 Hawaiian Art Guide

Introduction & foundations

Current page

Contemporary expressions

Experience GuideWorkshops & events

Threads of Mana – The Divinity in Featherwork and Fiber

To understand the art of the aliʻi (the chiefly class), my journey takes me to the hallowed halls of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum in Honolulu. Nothing can prepare you for the sight of the ʻahu ʻula (feather cloak) of King Kamehameha I. It radiates a golden light. A celestial garment carefully crafted from roughly 450,000 bright yellow feathers of the now-extinct mamo bird.

These were not mere garments. Known as nā hulu aliʻi (royal feathers), these cloaks, capes ('ahu 'ula), and helmets (mahiole) were deep symbols of the wearer's divinity, status, and spiritual power, or mana. The feathers, mainly sacred red and rare yellow, were so valuable they were collected as a form of tax.

Artist Spotlight: Marques Hanalei Marzan

My exploration of these sacred threads continues with Marques Hanalei Marzan. A contemporary fiber artist who holds the title of "Fiber Arts Knowledge Bearer." His connection to these traditions is uniquely intimate. He works in the cultural collections at the Bishop Museum. Literally caring for the ancestral treasures that inform his own art.

Marques bridges the past and future. He was trained in traditional weaving techniques by respected masters. But applies this knowledge to create innovative, sculptural forms. These incorporate modern materials like plastics alongside natural fibers.

He speaks of his great-grandmother, the last weaver in his family. Her hats he grew up admiring. Feeling a connection to a craft that was traditionally women's work. His process, whether preparing the long leaves of the hala tree or knotting coconut rope into complex forms, is a direct talk with the ʻāina.

Speaking with Marques reveals a deep truth about the role of cultural institutions. The museum is not a tomb where culture goes to die. For artists like Marques, it is a living library. A place of dialogue with the ancestors. The artifacts are not static objects but holders of knowledge. Providing the "source code" for new creation.

The construction itself was a sacred act. Bundles of feathers were tied to a fine netting made of olonā fiber. A process that was believed to tangle prayers into the garment. Offering spiritual protection to the chief who wore it.

These magnificent objects were also powerful tools of diplomacy. When the Hawaiʻi Island chief Kalaniʻōpuʻu first met Captain James Cook, he draped his own cloak over Cook's shoulders. A gesture of immense respect and a political act to forge an alliance.

This dynamic relationship challenges the colonial idea of the museum as a final resting place for indigenous culture. Instead, it becomes a bright hub where culture bearers consult with the past to innovate for the future. Making sure the threads of mana are woven into the present day.

The Gaze of the Gods – The Living Presence of Kālai

My final stop in understanding the foundational arts is at Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park. A sacred place of refuge on the Kona coast. Here, under the sway of coconut palms, stand the guardians: the kiʻi. These larger-than-life wooden figures are fierce and awe-inspiring. With powerful stances and piercing eyes made of shell.

These are not idols or statues in the Western sense. Kālai (wood carving) was a sacred practice. The kiʻi are physical forms of the akua (gods) and venerated ancestors. They serve as go-betweens, linking the material world to the spiritual realm.

Carved from native woods like ʻōhiʻa, they represent the great gods of the Hawaiian pantheon: Kū, the god of war and industry; Kāne, the god of creation; and Lono, the god of agriculture and peace. The act of carving them was reserved for a special class of priests, the kāhuna kālai kiʻi.

Today, the tradition of kālai kiʻi is being revived by cultural practitioners like James Kanani Kaulukukui Jr. He teaches that every cut and every detail must be carved with deep intention and respect. Making sure that the gods continue to have a watchful presence in the islands.

Continue Your Journey

Discover how these ancient foundations evolved into powerful modern expressions of resistance and resilience.

Explore Modern Hawaiian Art