E Hoʻi i ke Kumu

Returning to Hawaii's Cultural Source in a Modern World

An authentic journey into Hawaiian culture through Native Hawaiian perspectives

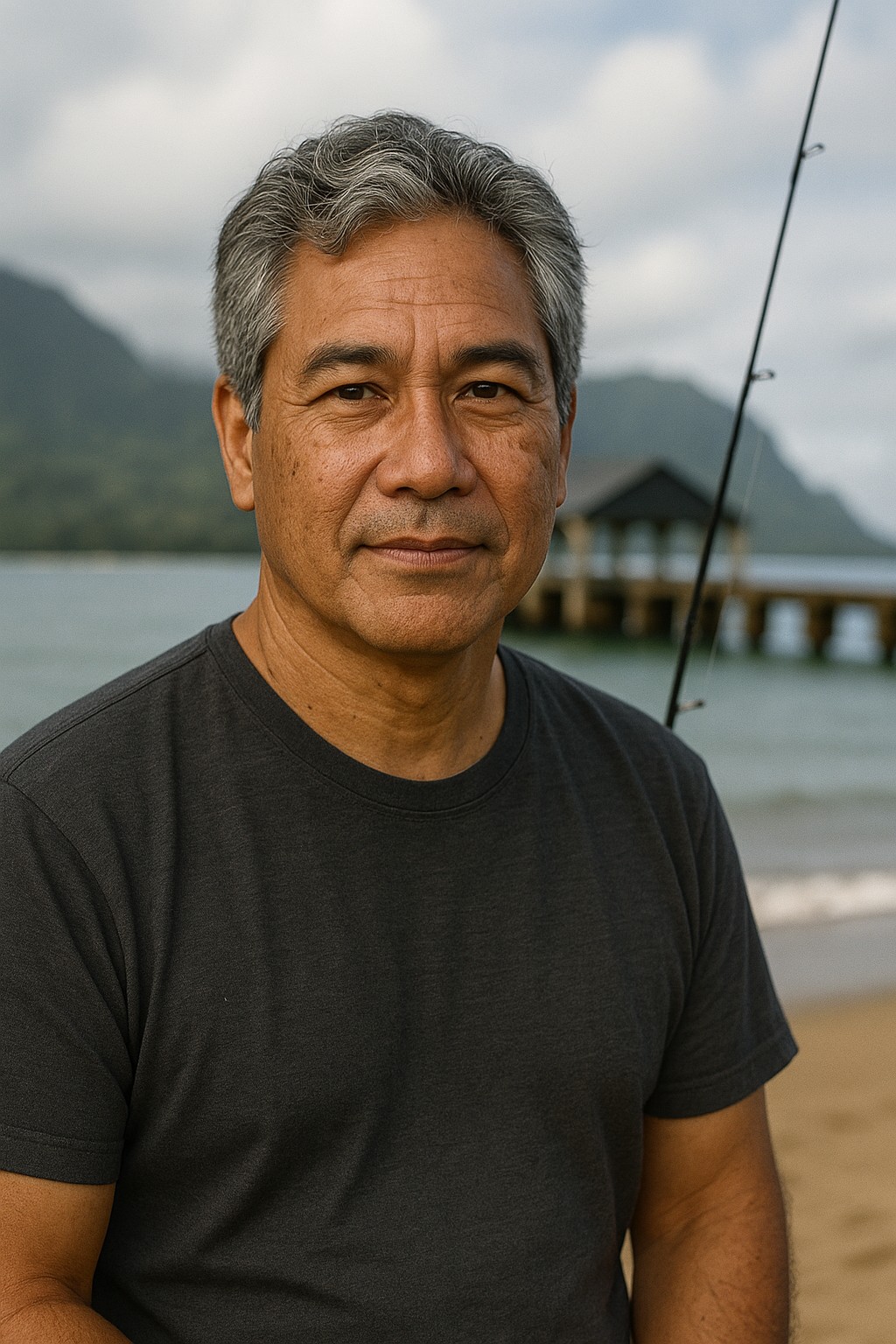

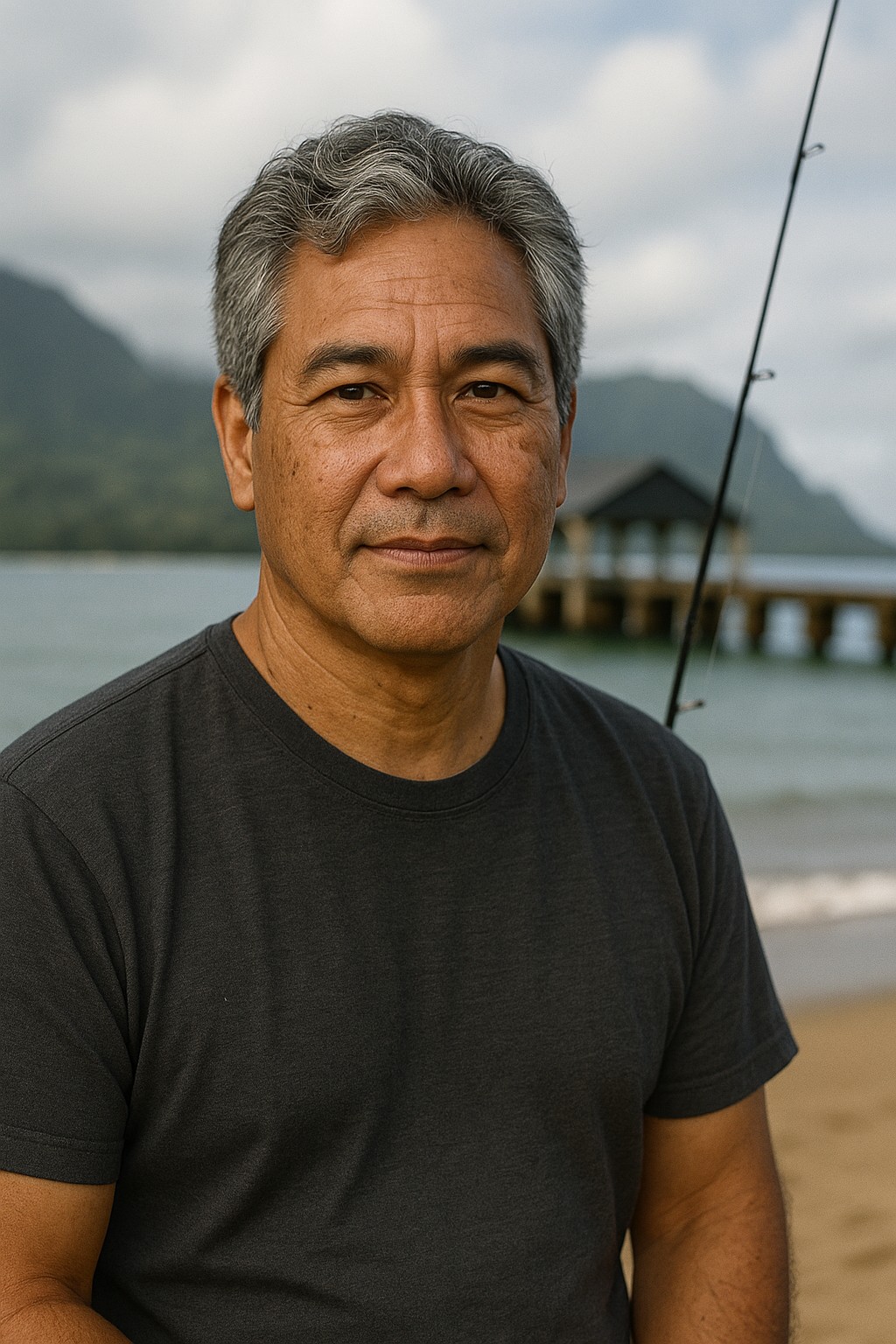

Written by Native Hawaiian Cultural Specialist

Kalani MillerThe sound that tells me I am home is not the gentle lapping of waves on a sun-drenched shore. It's not the strum of a ukulele drifting on a warm breeze. It is the deep, resonant beat of the pahu drum. A sound that travels not just through the air, but through the ground, through the soles of my feet, and into my bones. It speaks of lineage, of ceremony, of a connection to this ʻāina that is as old as the volcanic rock beneath us. It is the sound of Hawaiʻi's mauli, its life force. A pulse that is often unheard amid the cheerful din of tourism.

As a Kanaka Maoli, a Native Hawaiian, and a cultural specialist, I have the profound kuleana to share the stories of my home. This word means both privilege and responsibility. This is not the Hawaiʻi of glossy brochures, but a living, breathing entity with a complex history and a vibrant, resilient culture that continues to grow. For many who visit our shores, the experience is transactional. A photo is taken, a souvenir is bought, a memory is made. But to truly experience Hawaiʻi, to feel its heartbeat, is to enter into a relationship with it. It is to understand that the land is not a backdrop for your vacation, but an ancestor.

This article is an invitation to begin that relationship. It is a huakaʻi, a journey, into the heart of what it means to be Hawaiian. We will travel beyond the lūʻau and look for its cultural significance in the small backyard pāʻina. We will explore the foundations of our worldview, concepts that shape our every interaction with the world.

We will walk the land not as a collection of destinations, but as our ancestors did, through the ingenious system of the ahupuaʻa. We will meet the practitioners who are keeping our arts alive, listen to the stories that carry our history, and witness the powerful movements that are shaping our future. This is a journey to understand the foundational pillars of our culture: our sacred connection to the ʻāina, our expansive definition of ʻohana, and the stories that make us who we are. E hoʻi i ke kumu. Let us return to the source.

Part I: Nā Kumu – The Foundations of a Worldview

To understand any culture, one must first learn its language of being. The core concepts that shape its reality. For Kānaka Maoli, these are not abstract philosophies but lived truths, woven into the fabric of our daily lives. They are the roots that ground us, the source from which all else grows. To learn Hawaiian culture is to first understand aloha ʻāina, ʻohana, and the ancient system of kapu.

ʻAloha ʻĀina: The Land That Feeds and Defines

The phrase aloha ʻāina is often translated simply as "love of the land." While true, this translation barely scratches the surface of its profound meaning. It is a deep, reciprocal, and familial relationship. An understanding that the land, the ʻāina, is literally "that which feeds." It encompasses a worldview where people and land are not separate but part of a single, interconnected system of life. This is not a metaphor. It is our genealogy.

Our foundational creation story, the Kumulipo, tells of Papahānaumoku, our Earth Mother, and Wākea, our Sky Father. Their firstborn child, Hāloanakalaukapalili, was stillborn. From the sacred ground where he was buried, and watered by his mother's tears, grew the first kalo (taro) plant. Their second son, a human child, was also named Hāloa, in honor of his older brother. It is from this second Hāloa that all Hawaiian people are said to descend. This moʻolelo is the bedrock of our identity. It establishes the kalo plant as our elder sibling and the ʻāina as our direct ancestor. We do not just live on the land. We are of the land.

This ancient value is not a relic of the past. It is the animating force behind the most vital contemporary movements in Hawaiʻi. The modern struggle for Hawaiian sovereignty, ke ea Hawaiʻi, is inseparable from the spiritual and cultural responsibility to mālama ʻāina. When we see the land desecrated by military bombing, polluted by industrial runoff, or paved over for commercial development, it is not merely an environmental issue. It is a profound injury to our family, a violation of our most sacred relationship. The activism to protect sacred sites like Mauna Kea or Pōhakuloa, the fight for water rights, and the push for political self-determination are all modern expressions of aloha ʻāina. It is a practice of cultural survivance, a declaration that our connection to our ancestor, the land, will not be broken.

ʻOhana: The Unbreakable Circle of Relations

Just as our relationship with the land is familial, our concept of family is as expansive as the land itself. The word ʻohana has been popularized globally, often simplified to mean "family." But its true meaning, like aloha ʻāina, is rooted in the kalo plant. The word derives from ʻohā, the small offshoots or suckers that grow from the main kalo corm. These ʻohā are replanted to grow new plants, symbolizing the growth, regeneration, and interdependence of the family unit.

An ʻohana in Hawaiʻi extends far beyond the Western nuclear model of parents and children. It is a wide, inclusive circle that encompasses grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and, crucially, non-blood relatives who are considered family. Growing up here, it is common to be raised by a village of "aunties" and "uncles" who are not biologically related but who hold the same authority, love, and responsibility as any blood relative. This includes the beautiful practice of hānai, where a child is informally or formally adopted and raised by another family member or close friend. Not out of necessity, but as a way to strengthen bonds and share the joy and responsibility of child-rearing. Queen Liliʻuokalani, our last reigning monarch, was herself a hānai child.

Within this extended family, kūpuna (elders) are revered as the keepers of knowledge, the living libraries of our history, genealogy, and traditions. They are the bridge to our ancestors, and their wisdom guides the ʻohana. This structure creates a powerful support system where resources, responsibilities, and love are shared collectively. It's a common sight on the islands to see multiple generations living under one roof. Not just for economic reasons, but because it is the cultural norm to remain close, to care for one another from birth to old age. The popular phrase, "family means nobody gets left behind or forgotten," is a perfect, if simplified, encapsulation of this deeply held value. The ʻohana is the social embodiment of the interconnectedness we see in the kalo patch—a network of roots and shoots, all connected to the same source, all nurturing one another.

The Kapu System: Order, Mana, and Cosmic Balance

To understand ancient Hawaiian society is to understand the kapu system, a complex and powerful code of laws that governed every facet of life. The word kapu means "forbidden" or "sacred," and it established a framework of rules and prohibitions designed to maintain social order, regulate resource use, and, most importantly, protect and manage mana—the sacred, spiritual power that flows through all things.

The kapu system was a highly stratified structure. At the top were the aliʻi (chiefs), who were considered direct descendants of the gods and thus possessed immense mana. Below them were the kahuna (priests and master craftsmen), the makaʻāinana (commoners), and the kauā (outcasts). The laws dictated interactions between these classes, ensuring the sanctity of the aliʻi was not compromised. For example, it was kapu for a commoner's shadow to fall upon a high-ranking chief, an offense punishable by death.

One of the most defining aspects of the system was the ʻai kapu, or the sacred eating prohibitions. This set of laws dictated that men and women could not eat their meals together. Furthermore, women were forbidden from consuming certain foods that were considered the kinolau (body forms) of male gods. These included pork (a form of Lono), coconuts (a form of Kū), and most varieties of bananas (a form of Kanaloa). This religious and social order was dramatically overturned in 1819, shortly after the death of Kamehameha I. His son, King Kamehameha II (Liholiho), acting with the encouragement of his powerful mother, Keōpūolani, and his father's queen, Kaʻahumanu, deliberately broke the kapu by sharing a meal of forbidden foods with the women of his court. This single act, known as the ʻAi Noa (free eating), shattered the foundation of the ancient religious system and sent Hawaiian society into a period of immense transformation, paving the way for the arrival of Christian missionaries just a few months later.

While the kapu system may seem harsh to a modern observer, it also contained a profound wisdom of conservation. The laws regulated fishing, planting, and the harvesting of resources with a precision that ensured their sustainability. There were seasonal kapu on certain fish species during their spawning seasons, and prohibitions on harvesting from specific areas to allow ecosystems to regenerate. These practices are functionally identical to modern conservation strategies like establishing marine protected areas or implementing fishing seasons. This reveals that the contemporary ethic of mālama ʻāina is not a new concept born from the modern environmental movement. Rather, it is the continuation of a deeply ingrained conservation-oriented worldview, once enforced by the divine authority of kapu and now carried forward through the conscious choice and dedicated stewardship of our people.

Explore Hawaiian Culture

Dive deeper into the rich traditions, arts, and living culture of Hawaiʻi.

History

Journey through ancient Hawaii, kingdom years, and cultural renaissance

Art

Discover traditional and modern Hawaiian artistic expressions

Hula

The sacred dance that tells the story of Hawaii

Music

From ancient chants to contemporary Hawaiian melodies

Film

Hawaii's cinematic history and representation

Traditions

Sacred practices, customs, and Hawaiian ways of life

Luau

Traditional Hawaiian feasts and celebrations

Hawaiian Language Guide

Learn ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi basics and cultural context

Ahupuaʻa System

Ancient land management from mountain to sea

Living Arts

Continuing cultural practices in modern Hawaii

Sovereignty & Culture

Hawaiian self-determination and cultural resilience

📖 Cultural Guide Series

Current section

Land management wisdom

Part III: Living ArtsHula, kapa & healing

Part IV: SovereigntyCultural resilience today

🌺 Key Concepts

Love and care for the land as family

Extended family including non-blood relations

Rights, privileges, and responsibilities

Sacred spiritual power in all things

Sacred, forbidden, or restricted

🙏 Cultural Respect

- Acknowledge you are a guest in someone's home

- Practice noi (asking permission) at sacred sites

- Learn proper pronunciation of Hawaiian words

- Support Native Hawaiian-owned businesses

- Listen more than you speak

✍️ About the Author

Cultural Specialist

A Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) cultural specialist dedicated to sharing authentic Hawaiian perspectives and preserving traditional knowledge.

📧 Cultural Insights

Get deeper insights into Hawaiian culture and respectful travel practices.