.NqGFVS2I_ZeidDL.webp)

The Three Pillars

Kālai—The Sacred Art of Shaping Culture, Wood, and Stone

Written by a Native Storyteller

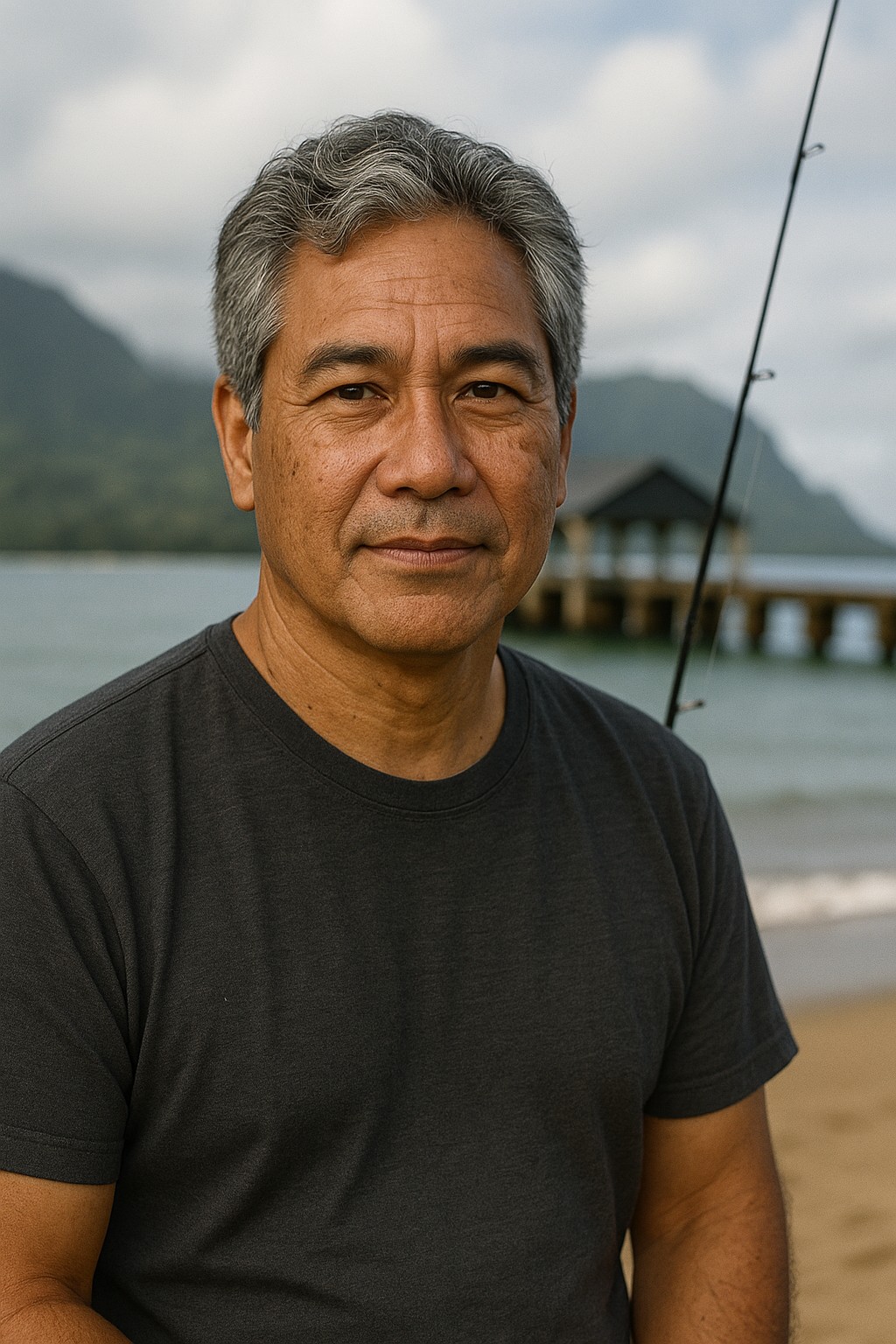

Kalani MillerKālai: The Shaping of a Man and a Movement

Tom's transformation from inmate to cultural guardian didn't start in the ocean. It began in the quiet of a library. While locked up, he "found books and higher learning," planting seeds for a new path.

After his release, he got a job as a lifeguard and enrolled in college. This academic journey would give him tools to explain the deep value of the culture he wanted to reclaim.

Finding Clarity in the Pōhaku (Stone)

His path led to the University of Hawaiʻi, where he earned a Bachelor's degree in Hawaiian Studies. He went on to get multiple Master's degrees in Pacific Island Studies and American Studies. Here he began to find the "clarity and unity" he'd been searching for his whole life.

School became his pūʻuhonua—a place of refuge and learning. It gave him historical context and a framework to understand why his culture had been pushed aside and, more importantly, how to bring it back to life.

During this time, he took the name "Pōhaku"—the Hawaiian word for stone. The name declared a new identity, one grounded and connected to the ʻāina (land).

Tom's academic work was brilliant in its strategy. Western education had often been used to erase indigenous knowledge. But Tom flipped this around. He used rigorous academic methods—research, thesis papers, advanced degrees—not to blend in, but to revive the very traditions that system had once called "backwards."

His Master's thesis on papa hōlua, the ancient sport of land sledding, wasn't just schoolwork. It was the foundation for bringing back a nearly forgotten practice. He was using the master's tools to rebuild his own house.

The Three Pillars of Revival

Tom's life work stands on three pillars of practice. Each is a form of kālai (shaping or carving) that brings ancient traditions back to life. These aren't separate hobbies but connected expressions of a single worldview where the spiritual and material can't be separated.

🏄♂️ Pillar 1: Heʻe Nalu (Wave Sliding) – The Spirit in the Wood

For Tom, creating a traditional surfboard, or papa heʻenalu, is a sacred ritual. It's a conversation between the craftsman and the spirit of the wood itself. The process starts long before the first cut, with careful selection of a native tree like koa, wiliwili, or ʻulu (breadfruit).

This is a dialogue. "Every wood speaks to you and talks to you," he explains, "and it tells you the type of board it is going to become." The goal is to find its kinolau—its body form—and restore its spirit.

The Sacred Process: The carving itself is a "connection between two spirits." The board gets shaped by hand, sanded with coral and sand, smoothed with sharkskin, and finally sealed with kukui nut oil—just as ancestors did for centuries.

Riding one of these boards is nothing like modern surfing. Heavy and finless, they demand a different relationship with the wave. To ride one is to experience a "harmonization between the wind, the motion of the water, the breaking of the wave."

Tom describes it beautifully: "When you stand up on a wood board, it's like listening to a beautiful symphony playing that's just soothing to your soul." It's a spiritual connection, a way to travel to "another place" outside of time, in communion with the elements and ancestors.

The Healing Circle: This practice reached its emotional peak in 1993, when Tom finally faced the memory of the burned board. From memory alone, he carved a replica of his father's creation from wiliwili wood. When finished, he buried it in a taro field—a ritual to let it absorb the color and mana (spiritual power) of the earth.

He then took the board to his ailing father. "What a moment that was," he says, the emotion still clear. It was healing, forgiveness, and the closing of a painful circle.

🛷 Pillar 2: Heʻe Hōlua (Land Sliding) – The Blood Sacrifice

While reviving wooden surfboard carving is significant, Tom is credited with an even bigger achievement—single-handedly bringing back heʻe hōlua, a practice that had nearly died out.

Hōlua is an ancient extreme sport that shows the incredible skill and bravery of the aliʻi (chiefs) who practiced it. It involves riding a papa hōlua—a narrow, 12-foot-long, 50-pound sled—chest-first down steep stone or grass slides at speeds up to 50 mph.

When Christian missionaries arrived in the 19th century, they stopped the practice, seeing it as "dangerous and barbaric." Knowledge of how to build and ride the sleds faded. The great slides that once marked island landscapes became overgrown and forgotten. Tom, through his academic research and hands-on work, brought it back.

"It's a blood sacrifice," he states, showing his calloused hands. "You bleed when you make the sled, and you bleed when you ride it." This isn't a complaint but a fact—recognition of the deep commitment required. The blood and sweat are part of the offering, part of breathing life back into this powerful tradition.

His revival of hōlua is a bold act of cultural reclamation, proving that his ancestors' spirit wasn't barbaric, but brave, brilliant, and worthy of deep respect.

🗿 Pillar 3: Kālai Pōhaku (Stone Carving) – The Stone That Shapes the Man

The third pillar of Tom's practice might be the most fundamental, since it's built into his very name. Kālai pōhaku, or stone carving, connects him to the bedrock of Hawaiian cosmology.

In the indigenous worldview, stones aren't dead objects. They're alive. They're kumu, or teachers. They're ancestors. They hold mana and memory. To disrespect a pōhaku is to risk spiritual consequences, because it's like disrespecting an elder or deity.

The Philosophy of Humility: Tom's approach to craftsmanship is deeply informed by this worldview. As master stone carver Hōaka Delos Reyes says: "It's not you who shapes the stone, it's the stone who shapes you."

This philosophy is the heart of Tom's work. The material isn't a passive medium to be controlled by the artist's will. It's an active partner in creation. The carver must listen, be patient, and let the stone or wood reveal its true form.

The process teaches the maker, giving strength to the weak and humility to the strong. For Tom, carving is an act of listening, a meditation, a way of connecting with the life force within all things.

🏛️ The Three Pillars

- Heʻe Nalu

- Traditional surfboard carving

- Heʻe Hōlua

- Ancient land sledding revival

- Kālai Pōhaku

- Sacred stone carving

🛠️ Traditional Materials

Sacred Hawaiian tree for boards

Lightweight for special boards

Alternative wood source

Living pōhaku teachers

🔄 Sacred Process

- Listen to the wood/stone

- Hand shape with adze

- Sand with coral

- Smooth with sharkskin

- Seal with kukui oil

The Unity of Three Practices

These three pillars aren't separate skills but interconnected expressions of a unified worldview. Each practice teaches patience, respect, and the art of listening to materials that are alive with spirit and history.

Spiritual Connection

Each practice connects the craftsman with ancestral spirits, natural forces, and the living essence within all materials.

Cultural Bridge

Through these ancient arts, Tom bridges the gap between traditional knowledge and modern understanding.

Living Tradition

Rather than museum pieces, these become living practices that continue to evolve while honoring their roots.

Through mastery of these three sacred practices, Tom didn't just learn crafts—he found his way home.

Each cut of the adze, each careful placement of cordage, each respectful touch of stone became an act of cultural healing, personal redemption, and spiritual connection to his ancestors.